People told me parenting would be hard. No one told me it might be because I wouldn’t feel particularly connected to my own child. Or that shaming myself into silence for feeling that way would only make it harder.

It was the 4th of July. After struggling to hand-feed my stubborn 14-year-old diva Shih Tzu that morning, I slowly (dramatically) collapsed to the floor in front of my kitchen sink.

And I sobbed. No feat of strength could compel me to rise up off the floor, where I lay for 15 minutes. For better or worse, I knew that clamming up about those feelings had failed me long before my face was pressed to luxury vinyl planking because my dog wouldn’t eat her diet-sensitive all-natural food (side note, LVP is a fine surface for crying, should you need it).

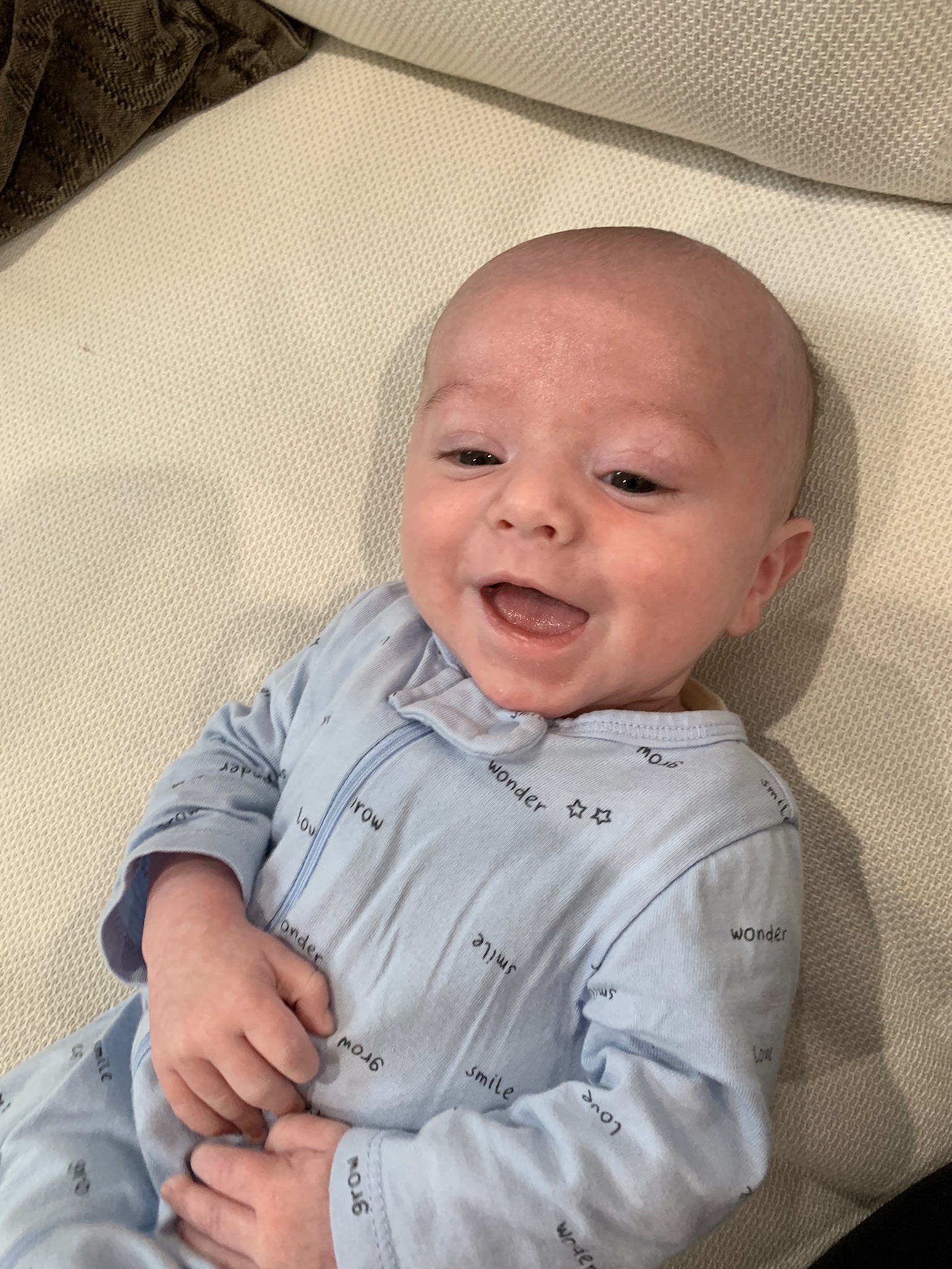

Parenthood is sold as a Pantone parade of fluffy shades of pink and blue. If there’s an obstacle, its antidote is found in the mundane achievements of your cooing offspring. You slept two hours last night? What a cute baby, look at him stretch! He screamed for 40 minutes and won’t take a bottle? Look at him stare at the little bear on his play mat! Your business is going through significant changes and you’re suffocating under the weight? Look how cute he is in that green swaddle that makes him look like a string bean!

Now read him another book and narrate it in baby talk. Rinse. Repeat.

In the days after my meltdown, I found myself standing on our floor instead of laying on it. Little victories. And as my shame transformed into generic angst, I started telling friends with children of their own about what had happened to me. Or rather, what was still happening to me, even if I was upright more often.

Not one of them was surprised. In fact, I was stunned to learn that something similar had happened to most of them, as if crying on the floor in the early stages of fatherhood is Fight Club, and the first rule of Fight Club is that we don’t talk about it.

I have a marginally better explanation for my distress now. But I quickly learned that once I’d said this shameful thing out loud — that I didn’t feel close or connected to my own son — that the power it held over me started to dissipate. The overwhelming insecurities and self-doubt started to feel rational instead of suffocating.

It was hardly an overnight transformation, but it was a start. Then two days later, I heard my wife talking to our son through the audio on the baby monitor, a common event when he’s waking up from naps.

“You’re always smiling when you wake up, sweet boy! You like your naps?” she said.

I knew what she was talking about because I’d seen it myself. Whether this boy had gone to sleep with ease or fighting us like a scene out of Gladiator, sure enough, he’d wake up from his nap smiling and cooing. As if the best moment of his day is always this one.

I knew what she was talking about because I’d seen it myself. Whether this boy had gone to sleep with ease or fighting us like a scene out of Gladiator, sure enough, he’d wake up from his nap smiling and cooing. As if the best moment of his day is always this one.

I felt a pang of embarrassment again — and trust me, I’m working on it — as I realized this little boy is oblivious to anything except what is. He is aware only of his bottles, his bed, and his mommy and daddy. Everything else is noise.

I sat with it.

And somewhere in my dense 36-year-old brain, the one that’s been conditioned to dumb down its purpose to that of a provider and cog in the capitalist wheel, a light flickered. And my wife’s voice repeated itself to me: “You’re always smiling when you wake up, sweet boy!”

Why? Why is this kid smiling?

Okay, so I don’t know this with total certainty, but I’d venture that it’s because of this —

His mind is not molded or compromised by what adults think they know about the world, or what even his own teachers or peers might project onto him in the realm of expectations, doubt and fear. He knows food, sleep and love. That’s it.

I almost gave in to the temptation to write it off as his naïveté because after all, he is just a baby. But him not knowing better is in fact his super power. Me thinking I know better has undoubtedly been my kryptonite. As I peeled back the root of my angst, I realized (with some help from my therapist) that my son was actually a much smaller source of my frustration than I’d first thought. In truth, he’d just represented the newest thing I couldn’t master or bend to my will. On the growing list of things that have rendered me less-than, the common theme has been difficulty with the gap between what is and what might be.

The light in my mind flickered a bit brighter, and with it, the realization that what could be is a figment of my imagination. It’s a diversion, a guess and a distraction. My waking hours have been littered with them, distractions.

I don’t wake up smiling. I wake up in fear of not having enough, of second guessing my decisions at work. Of how I’ll buy my next house, or what trips I’ll take to escape from a reality I haven’t bothered to understand, let alone embrace.

I was a boy once too. I think back on my own father, and I am reminded that I didn’t know what working class was, and if I did, I wouldn’t have cared. Dad’s money didn’t matter to me. I was oblivious to his shortcomings. And what I loved about my dad is that he loved me and had time for me.

I was a boy once too. I think back on my own father, and I am reminded that I didn’t know what working class was, and if I did, I wouldn’t have cared. Dad’s money didn’t matter to me. I was oblivious to his shortcomings. And what I loved about my dad is that he loved me and had time for me.

I think that’s what innocence is. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve unconsciously used innocence as a synonym for being naive. I am wrong for that. Innocence is part purity, part simplicity, and perhaps it’s best defined as the intersection between the two. I am envious of my son’s innocence in part because it reminds me that I’ve lost mine.

But maybe the way back to it is through him. I could learn a thing or two from someone who always wakes up smiling.